Adaptations

Other Adaptations

Foraging - Finding Food

Echidna

The echidna (Tachyglossuss aculeatus) has notable morphological adaptations to foraging, with mouthparts that are highly modified to find, collect and eat its diet of ants and termites. It has

• an elongated tube-like snout that function as both mouth and nose, and contains electro-sensors. These are cells that respond to electrical stimuli emitted from the presence of ants underground and termites inside the mound.

• long, strong claws for digging into termite mounds

• a mouth with no teeth.

• a long sticky tongue for exploring and capturing ants and termites, grinding them between the tongue and the bottom of its mouth. Watch the echidna feeding on National Geographic WILD at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHjdIXN9v2g

Antlion

The antlion (Family, Neuroptera) is the larval form of the Lace-wing fly, and the most effective sit-and-wait predator in the animal world, relative to body size. Its technique has been much studied by scientists and is an ideal subject for students to be introduced to basic mathematical and physical concepts, such as angles and the forces of motion (momentum).

Catching an animal by digging a pit in the ground’s surface is a well-known trapping method.

But to wait, buried at the bottom of the pit for food to arrive, hold it, inject a toxin, digest the contents, then toss out the remains, requires some ability - and the following morphological adaptations. It has

• a very plump abdomen, which helps to anchor it in its pit

• a pair of large sickle shaped jaws that contain the maxillae and the mandibles fused together, forming a canal through which venom is injected

• 3 pairs of legs, the hind pair extended for digging

• forward pointing bristles that anchor it in its pit when struggling with its prey of ants

• a head region modified to act like a bucket for throwing sand

• injecting a toxin is a physiological adaptation

Watch the antlion in action at

http://www.antlionpit.com/antlions.html

Follow the prompts to the antlion behaviour and life cycle.

Short-beaked Echidna. Tachglossus aculeatus Photo: Gunjan Pandey

Antlion

Predation and How to Avoid it

Plants

• Plants are a rich source of food for most animals; they have evolved both morphological and physiological adaptations to deter animal predation.

• Leaves and stems that are spiny, such as cacti, and spinifex spines that contain silica, a compound found in quartz rocks and sand, may deter some from animal predation, but not all!

• Leaves make chemical compounds, phenols, that make them unpalatable to herbivores.

• The phenol, fluoroacetate, produced in the seeds of Gastrolobium and Oxylobium species, is highly toxic, both to humans and ruminant animals.

ANIMALS

• The Ornate dragon (Ctenophorus ornatus) is morphologically adapted to its habitat. Restricted to granite outcrops, its flattened body allows it to find refuge from night-time predation in the narrow space under exfoliated rock on the granite’s surface.

• Another morphological adaptation is the dragon’s colour. It has 2 colour forms, each resembling the colour of its granite habitat. ‘Red’ forms are found on red granite (see photo), and ‘black’ forms are found on dark granite (see photo). This is called ‘camouflage’ and protects the lizard from daytime predation by birds.

• The Mountain devil (Moloch horridus) is also camouflaged by its thorny scales. These break up its body outline, visible to a predator hovering above.

• The Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) has long body spines, also designed to deter predation.

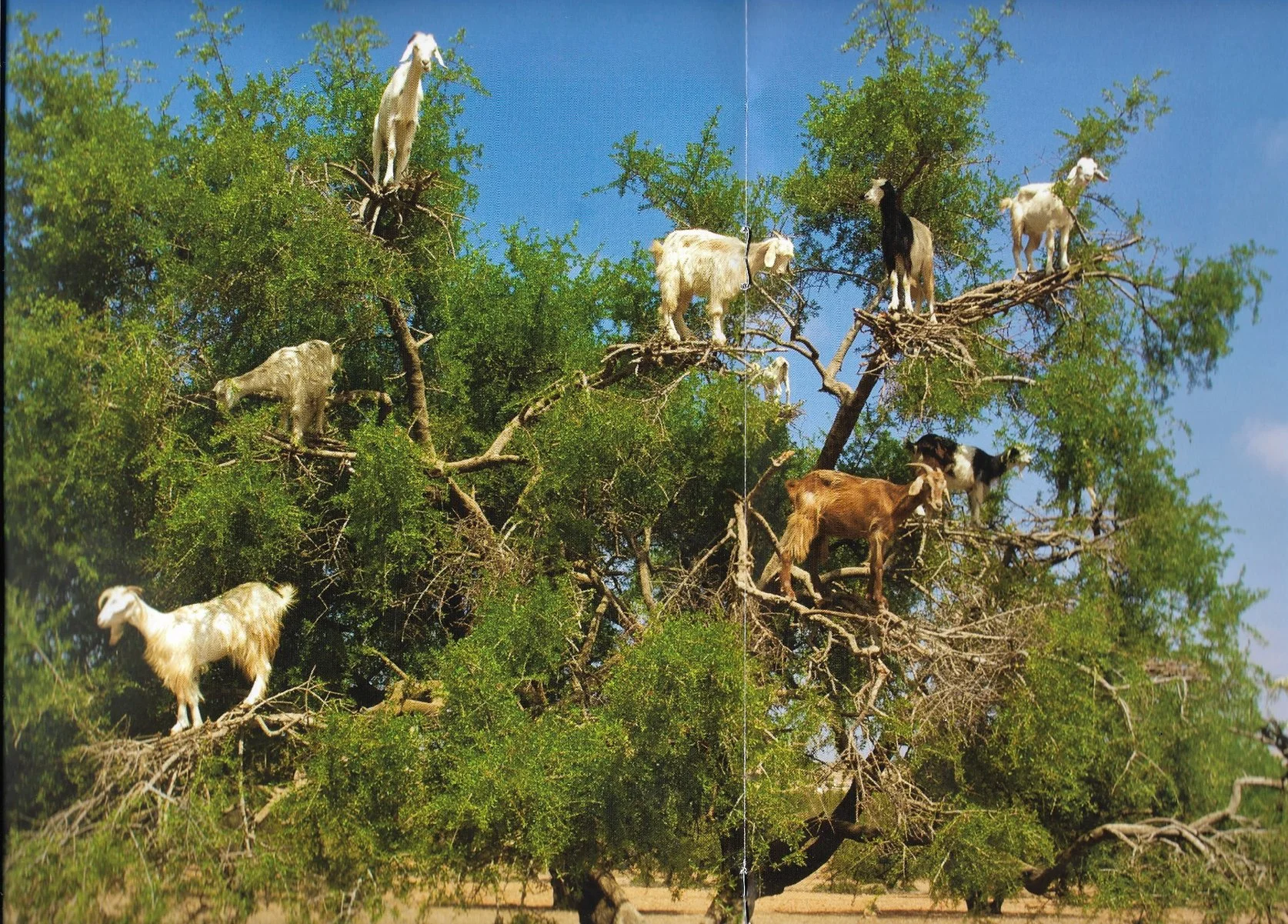

Goats in a spiny desert wattle tree

C. ornatus, dark form

C. ornatus, red form

Conserving Energy

• When food is scarce, the echidna has a physiological adaptation to conserve energy. Its body temperature of 29 - 32°C is lower than the 37°C of other mammals. This was once thought to be a primitive characteristic, but is now considered an adaptation to conserving energy.

• Working with the short-beaked echidna in the Wheatbelt, Christine Cooper and colleagues discovered the ability of the echidna to lower its body temperature to 11 oC (or even lower) for several days, following a fire.

• These short bouts of a reduction in body temperature (1 to 3 days) is called torpor, and allows the animal to conserve energy when food supply may be low (6).

• It is not to be confused with hibernation or aestivation. These are prolonged periods of lowered body temperature in extremely cold or hot climates.

• Scientists also found echidnas in their shelter (hollow log or in surface soil) when the environmental (ambient) temperature was 59 oC., a temperature that would be lethal for an echidna. This is a behavioural adaptation to avoid high temperature.

In summary, the echidna is a highly adapted animal.

• it has a wide tolerance of temperature fluctuation

• a spine-covered body to deter predation

• mouthparts finely attuned to a diet of ants (the most prolific insect on Earth) and termites.

• when food is scarce, the ability to conserve energy by undergoing periods of torpor.

It is perhaps no wonder that this animal is the most widespread native mammal in Australia.

Activity

Describe and identify an adaptation as morphological, behavioural or physiological in the plants and animals listed in Worksheet 1 (TOOLBOX)

Activity

List the morphological, behavioural and physiological adaptations in the echidna, a lizard, the antlion and a wattle tree, indicating the selective force operating in each case. Worksheet 2 (TOOLBOX).